An evidence-backed opinion guide for LakeNakuru.org

Lake Nakuru’s flamingos don’t “disappear” because they got bored of Nakuru. They move because Nakuru’s soda-lake engine—the chemistry that grows their food—keeps getting knocked out of its operating range, and because we’ve built a catchment that increasingly delivers the wrong kind of water and the wrong kind of pollution at the wrong time.

The most important point to hold onto is this: for Lesser Flamingos, Lake Nakuru is primarily a food system, not a scenery system. When the food collapses—or becomes toxic—flamingos leave. When the network of suitable lakes shrinks, the whole population becomes more vulnerable.

1) Hydrology shock: rising water levels dilute the soda-lake recipe

Threat mechanism: Lake Nakuru’s productivity depends on its alkaline–saline conditions that favor cyanobacteria (notably Arthrospira). When water levels rise sharply, the lake can become less saline/less alkaline, shifting phytoplankton communities and reducing the dense blooms flamingos rely on.

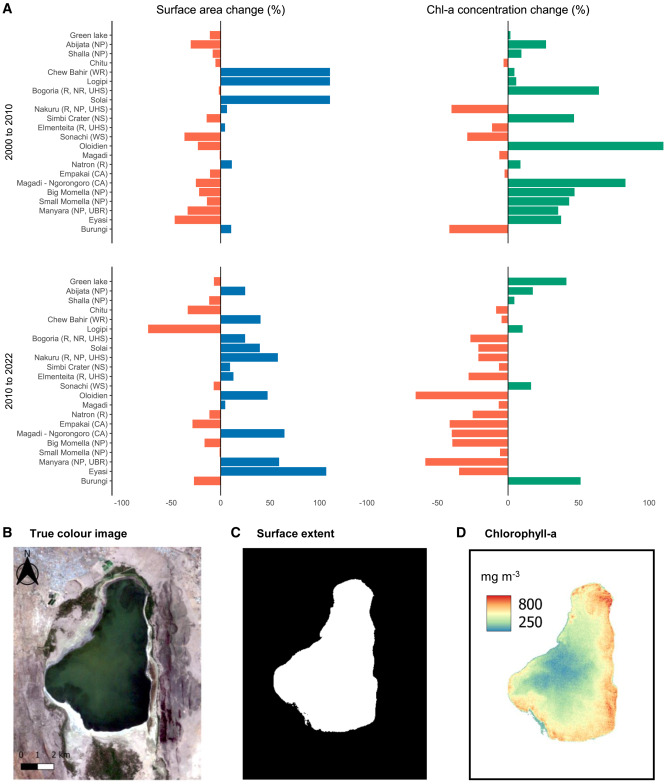

What the best recent evidence shows (region-wide, including Nakuru):

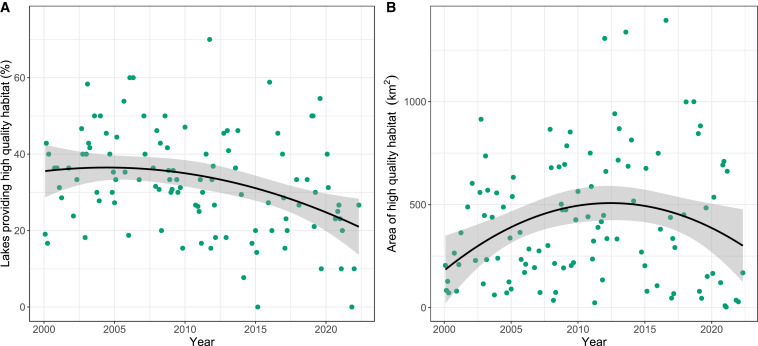

- Across 22 East African soda lakes, phytoplankton biomass (chlorophyll-a) declined significantly from 1999–2022, while lake surface area (a proxy for water levels) increased—especially post-2010.

- The same study highlights Nakuru’s scale of change: surface area +90.7% (2009→2022) alongside a major drop in chlorophyll-a.

- The broader Rift Valley trend of rising lakes is widely reported, with climate variability and increased rainfall among the leading drivers (with land-use change often compounding runoff/sedimentation impacts).

Why this is the “master threat”: If the lake is frequently pushed outside its chemical comfort zone, Nakuru becomes unreliable as a feeding lake. And a nomadic specialist can cope with variability only if the wider network still contains enough good alternatives; the paper shows that the number of high-quality feeding lakes is declining.

LakeNakuru.org stance: Climate-driven hydrology is not an excuse to do nothing. It’s exactly why catchment governance matters more than ever—because we can’t manage rainfall, but we can manage what that rainfall becomes when it hits farms, roads, sewers, and river channels.

2) Sewage and stormwater: “nutrients” are not always the problem—sometimes it’s outright toxicity

Nakuru’s catchment doesn’t just deliver water; it delivers urban effluent, organic loading, plastics, oils, and chemicals—often via stormwater pathways and wastewater systems under strain.

Evidence signals to take seriously:

- A conservation outlook assessment for the Kenya Lake System notes weak sewer connectivity and treatment performance concerns, with references to high BOD loadings and the detection of cyanotoxins in sewage treatment ponds linked to Lake Nakuru—dangerous if wildlife drinks contaminated water.

- Earlier lake basin documentation describes substantial daily sewage generation and discharge pathways, and the reality that not all waste is effectively captured before reaching the lake environment.

- Reporting from Kenyan media during high-water periods has warned that flooding can disrupt sewage infrastructure and increase the likelihood of untreated waste entering the lake.

Why this matters for flamingos:

Flamingos are filter-feeders. They cannot “choose” clean water the way a grazing antelope can choose a different grass patch. If the lake concentrates the wrong compounds—especially toxins associated with harmful blooms or effluent inputs—the birds can be exposed at scale.

LakeNakuru.org stance: The debate shouldn’t be “is sewage a problem?” It should be “why is a World Heritage-level lake system still receiving avoidable pollutant loads?” (And yes—stormwater is often the silent delivery mechanism.)

3) Harmful algal blooms and cyanotoxins: when the bloom turns from food to poison

A critical nuance: not all cyanobacteria are equal. Flamingos depend on specific food resources (notably Arthrospira in many soda-lake contexts), but soda-lake systems can also host toxin-producing cyanobacteria under certain conditions.

What the literature shows:

- Mass mortalities of Lesser Flamingos in Kenyan Rift Valley lakes have long been associated (as plausible causes) with algal toxins (including microcystins), heavy metals, pesticides, and infection/malnutrition—i.e., a multi-stressor mortality landscape, not a single smoking gun.

- A widely cited analytical study detected cyanobacterial toxins (microcystins / anatoxin-a) in materials linked to Lesser Flamingo mortality events, supporting cyanotoxins as a credible pathway of harm.

- A broader review of harmful algal bloom effects on birds notes recurring die-offs of Lesser Flamingos at Rift Valley lakes including Nakuru and Bogoria. Read about Lake Nakuru Birds here

How this threat interacts with water levels:

Counterintuitively, both “too wet” and “too stressed” states can elevate risk—because shifts in salinity/alkalinity, temperature, mixing, and nutrient/organic inputs can reorganize microbial communities and bloom dynamics.

LakeNakuru.org stance: Treat cyanotoxin risk like you’d treat cholera risk in a city: you don’t wait for a catastrophe to “prove” it matters. You build routine monitoring, early warning, and response capacity.

4) Industrial and agricultural contamination: heavy metals, pesticides, and persistent pollutants

The Rift Valley soda lakes sit in human landscapes. Around Nakuru, the combination of industry, dense settlement, and intensive agriculture increases the probability of trace metals and pesticide residues entering the lake via rivers and stormwater.

What the evidence base says (at least at the level of risk):

- The international Single Species Action Plan for the Lesser Flamingo explicitly lists large-scale die-offs being attributed (in different events/places) to industrial heavy metals, pesticides, and other pollutants, alongside habitat issues and disturbance.

- The “multi-cause” framing in Rift Valley mortality literature repeatedly includes heavy metals and pesticides as plausible contributors.

Why it’s hard to communicate:

Because “metals and pesticides” are rarely visible to visitors. The lake can look beautiful right up until it doesn’t. But long-lived birds can accumulate pollutants, and episodic spikes can do acute damage.

LakeNakuru.org stance: This is exactly why the catchment must be managed as a single system—industrial compliance, farm chemical practices, riparian buffers, and wastewater performance all converge at the lake.

5) Habitat disruption around the lake edge: lost shallows, altered shoreline, and disturbance

Flamingos need more than food. They need accessible feeding shallows, safe roosting zones, and low-disturbance space—and those are shaped by water levels and human activity.

Key pathways:

- Shoreline flooding can drown or shift shallow feeding zones and change where birds can safely roost.

- Vehicle pressure and tourist behavior (especially approaching flocks too closely) increases stress and can reduce feeding efficiency—an issue recognized in earlier conservation assessments of flamingos in the region, including mentions of disturbance at Lake Nakuru.

- Infrastructure on lake margins (roads, fences, utilities) can fragment quiet habitat and intensify disturbance footprints.

LakeNakuru.org stance: Disturbance is not the biggest threat—but it becomes a bigger threat when food is already marginal. When birds are hungry, they can’t afford to waste energy being flushed repeatedly.

6) Disease and mortality events: the “secondary threats” that explode under stress

When lake conditions deteriorate, birds become more susceptible to disease and mortality cascades. Literature discussing Rift Valley flamingo die-offs frequently treats disease alongside toxins and pollutants (rather than as an either/or).

Practical interpretation:

Don’t ask whether toxins or disease killed birds. Ask what pushed the system into a state where mass death becomes possible—and why we weren’t measuring it in time.

The threat hierarchy for Lake Nakuru (a blunt, usable ranking)

- Hydrology-driven chemistry change (rising water levels + dilution of soda conditions)

- Catchment pollution load (sewage + stormwater + industrial/ag inputs)

- Cyanotoxin / harmful bloom risk and mortality events

- Disturbance and shoreline habitat pressure (amplifier under stress)

- Disease and multi-stressor die-offs (often a downstream outcome)

What “good management” looks like (and what we should stop pretending is enough)

A. Measure the right things, routinely

A lake that supports iconic wildlife should not be flying blind. The minimum monitoring package should include:

- chlorophyll-a and phytoplankton community indicators

- salinity, pH, conductivity (core soda-lake chemistry)

- cyanotoxin screening during risk periods

- wastewater performance indicators (BOD/COD) + stormwater hotspot sampling

B. Treat the catchment like the park’s “invisible half”

The lake is downstream of everything:

- upgrade sewerage and prevent flood-related bypasses

- enforce industrial discharge compliance

- reduce agricultural runoff with riparian buffers/wetlands and soil conservation

The conservation outlook assessment explicitly emphasizes catchment-related pressures and the need for better management of runoff and waste pathways.

C. Manage tourism behavior as a conservation tool

Not “ban tourism”—manage it:

- distance and speed controls near large flocks

- designated viewing points and seasonal buffer zones

- guide standards that treat feeding flamingos as a sensitive resource, not a photo prop

A closing argument from LakeNakuru.org

Lake Nakuru’s flamingos are not a permanent exhibit. They are a diagnostic signal. When they leave, it’s not a tourism problem—it’s a systems problem.

If we want flamingos to remain part of Nakuru’s identity, we must stop managing the park as if it ends at the fence line. The real battlefield is the catchment, the sewer network, the storm drains, and the land-use decisions upstream. The science is already telling us the soda-lake network is losing high-quality habitat as water levels rise and productivity declines